Today our creative prompt comes from Bonnie Whiting, Chair of Percussion Studies and an Assistant Professor at the University of Washington School of Music.

What we’re making today

Today Bonnie is asking us to create a text that we’ll use to guide a musical performance. Bonnie is well-known for her performances of works for speaking percussionist, where she talks or sings while playing her instruments. This is one way to approach this prompt – speaking our text while playing – or we can use the text as inspiration for the music and sounds we’ll play in our new piece.

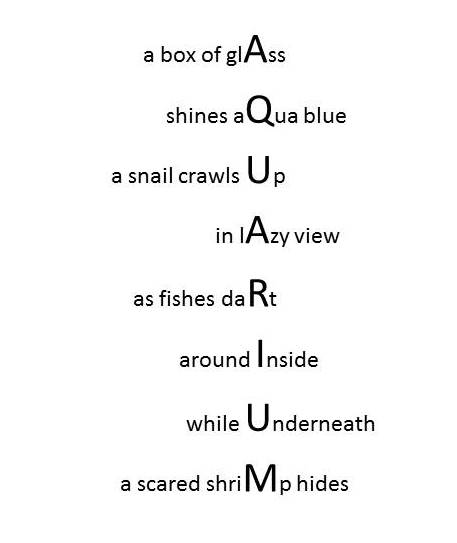

As a first step, today we’ll be making a mesostic poem. This is a poem where we have a title that runs vertically down the page, and then horizontal lines of words that run through the title. For an example, take a look at Australian poet Celia Berrell’s mesostic poem “Aquarium”. (This particular poem has some rhyming elements, but we won’t be looking for this in our poems).

To get started, you’ll need to choose your title, which will be the ‘spine’ of your poem. This could be your name, a favourite line from a song or poem, or you could use an online random phrase generator to come up with something surprising! You’ll then need to collect five books or magazines from around your house.

Write your spine vertically down a piece of paper, then take your first book or magazine. Look for a sentence or small group of words that includes the first letter of your poem’s spine. Write this sentence through the spine, then continue on to the next letter in the title and the next book. Continue cycling through your five texts until you’ve found a sentence for every letter of your spine.

Once you have your poem, we’ll need to make some decisions about how to perform it! Yesterday we looked at how we could take inspiration from poetry to create new musical pieces. We can use these approaches to work with this new poem we’ve created today, thinking about ideas like sound-painting, moods and shapes. Bonnie also suggests trying to speak your poem out loud while playing, or to use your poem as lyrics and sing your text. This can require some coordination and planning, but is a really great skill to develop!

Today your responses will include both your poem and your musical response, in either audio or video form. Please make sure your name is in the title of your files so we know who to credit!

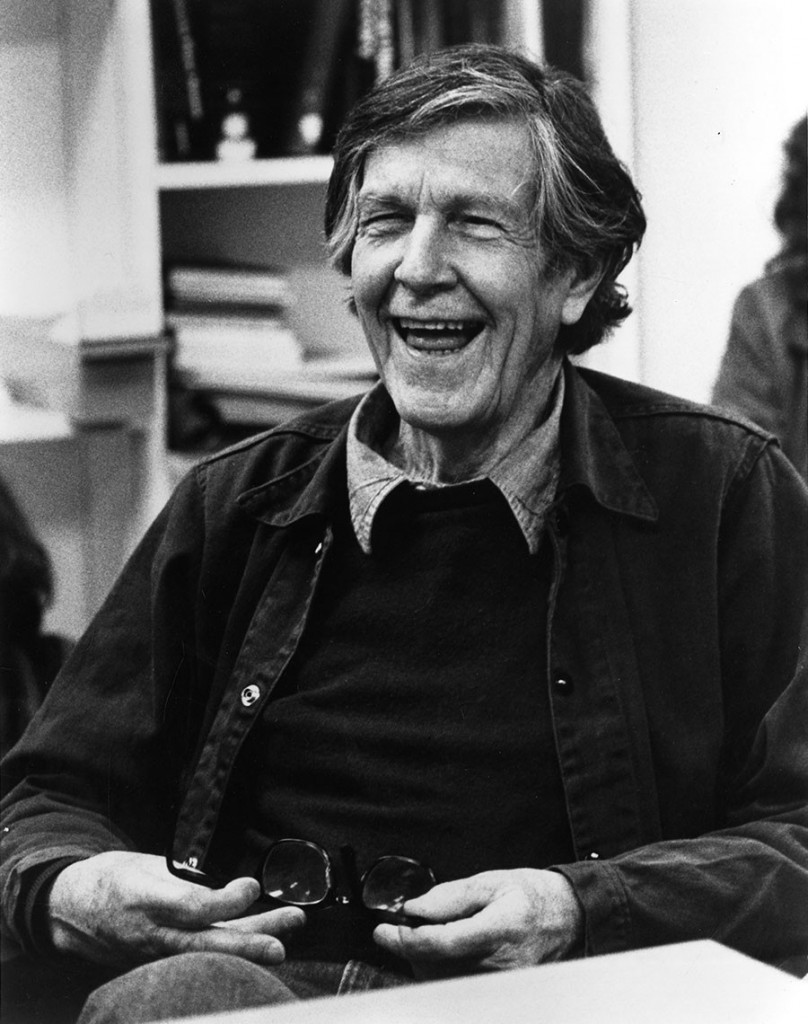

Bonnie Whiting

“. . . the feat of covering both vocal and instrumental roles at the same time is an impressive tour de force. Listening to it is like imagining a lecture on modern music in a room occupied by a crazy robotic drum corps.”

— Second Inversion

Bonnie Whiting performs, commissions, and composes new experimental music for percussion. She seeks out projects involving non-traditional notation, interdisciplinary performance, improvisation, and the speaking percussionist. She lives and works in Seattle, WA, where she is Chair of Percussion Studies and an Assistant Professor at the University of Washington School of Music.

Her debut solo album, featuring an original solo-simultaneous realization of John Cage’s 45’ for a speaker and 27’10.554” for a percussionist, was released by Mode Records in April of 2017. Her second album, “Perishable Structures” launches in August of 2020 and places works for speaking percussionist within a context of storytelling. Recent projects include performances as a percussionist and vocalist with the Harry Partch Ensemble on the composer’s original instrumentarium, and a commission from the Indiana State Museum’s Sonic Expeditions series for her piece Control/Resist (2017): a site-specific work for percussion, field recordings, and electronics.

2021 brings the premiere of Through the Eyes(s): an extractable cycle of nine pieces for speaking/singing percussionist collaboratively developed with composer Eliza Brown and nine incarcerated women, and the world premiere of a new percussion concerto by Huck Hodge with the Seattle Modern Orchestra.

For more on Bonnie, visit www.bonniewhitingpercussion.com/.

Extra Credit

Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us.

— John Cage

When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.

Today’s prompt is inspired by the work of John Cage, a hugely important and influential figure in 20th century music. Cage was particularly interested in:

- extended techniques: finding new, non-traditional ways to play or sound instruments

- electroacoustic music: using technology to alter the sound of acoustic instruments

- indeterminacy: a way of composing that leaves some parts of the performance up to chance, or asks the performer to choose an outcome

One of Cage’s best-known works is 4’33” (1952). This piece is four minutes and thirty-three seconds long, and the performer(s) are asked not to make any sounds. Instead, the piece is made up of the sounds the audience hears during that time – chairs squeaking, birds, traffic outside. Cage was interested in the idea of how we classify sounds as musical or non-musical – or if this difference even really exists.

As Slow As Possible

In September 2001 in a church in the German town of Halberstadt, a performance of a remarkable piece by John Cage began. ‘As Slow as Possible’ is a work for organ that asks the performer to test the limits of just how slowly they can play. Cage never specified exactly how slow he meant for the piece to go, leading to many discussions between musicians and philosophers about what the tempo should actually be!

Musicians have given solo performances lasting for eight, fourteen or even twenty-four hours, but in 1997 a plan was hatched to create a version for a specially-built instrument that would last for a staggering 639 years, ending in the year 2640.

This year a crowd gathered on September 5 to hear the first chord change in the piece in more than six years. The next change will take place in February 2022, and the next in February 2024. You can see the one-of-a-kind instrument below, and read more about this project here.

Prepared Piano

Cage’s music has challenged many of our ideas about how music exists in the world, including our ideas of what an instrument is and how we should play it. For percussionists, Cage would write for tin cans and car parts as well as more familiar instruments. When it came to the piano, Cage worked with preparations to radically change the sounds it could make.

Preparations are temporary alterations to your instrument that change the sound. Examples include adding small balls of blu tack to a violin’s strings, adding paper under a flute’s keys to create a buzzing/rattling sound, or using strings of paper clips on cymbals for a sizzle effect. You want to be careful not to damage your instrument, and your teacher will be able to advise you if you want to explore these sounds!

In this video, pianist-composer Nahre Sol explains and demonstrates some of Cage’s favourite piano preparations, metal or wood screws and rubber straps carefully placed in the piano’s strings. This is an excellent demonstration of how these objects change the piano’s sound.